By doctor and Indigenous healer Lewis Mehl-Madrona.

Since the earliest days of the epidemic I have known and worked with people living with HIV/AIDS. I was a family physician in San Francisco before the virus was even identified as HIV and well into the contemporary times of effective antiretroviral drugs. In the early ’80s, many of us had identified a terrifying disease that was stalking predominantly gay men. I remember encounters with the spirit of that disease being among the most frightening I have ever experienced. We struggled to make sense of what was happening.

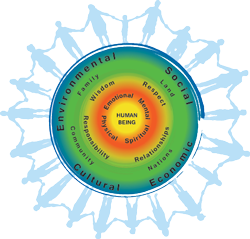

People who are schooled in the biomedical approach to health (as I have been) frequently ask me how traditional healers treat specific diseases. I struggle to explain how traditional North American medicine more closely resembles Chinese medicine than contemporary biomedicine. Traditional Elders approach the person as an integrated whole. Health is restored through restoring balance among mind, body, spirit and community. Elders focus more on the person and how to restore harmony and balance for them, rather than treating the disease as it is defined by Western biomedicine.

|

|

The differences between traditional healing practices and biomedical medicine deserve highlighting. Traditional practices emphasize communication with spirit beings and direct requests for healing. This communication occurs through prayer, song and ceremony. Additionally, one looks for areas of disharmony and imbalance within the external community, within the community of one’s mind, and in the relationship with our bodies, the earth, the plant people, the animal people and all of creation. Healing is achieved through achieving balance and harmony in our many relationships. The approach to each person is different because each person is unique and has their own set of imbalances. By contrast, biomedicine generally looks for the one treatment that will benefit the highest number of people with a particular disease, such as HIV.

But the two approaches are not incompatible. Mi’qmaq Elder Albert Marshall, of Sydney, Nova Scotia, introduced the term two-eyed seeing to describe the idea that the Indigenous and scientific approaches can co-exist. Certainly, the scientific approach has made great headway with HIV—contemporary antiretroviral drugs are highly effective and have transformed the shape of the world of HIV. Nevertheless, the traditional approach still provides benefit to those who use it, above and beyond antiretrovirals.

My childhood was immersed in my grandmother’s and great-grandmother’s traditional healing practices. Despite my interest in science, I never doubted the validity and importance of how they lived and what they practiced to help members of their community get well.

HIV in Indigenous communities

So, where are Indigenous communities today when it comes to HIV? Indigenous people are over-represented in the HIV epidemic in Canada: Although Indigenous people made up only 4.9 percent of the general population in 2016, they accounted for 9.6 percent of people living with HIV and 11.3 percent of the estimated 2,165 people in Canada who received an HIV diagnosis that year.

The challenge lies in getting people tested, encouraging them to get on HIV treatment and stay connected to care despite the many social factors that mitigate against doing so.

Social issues

The social factors that affect people’s health are extremely important. For example, Indigenous people face more poverty, violence, stigma and discrimination, substance use, sexually transmitted infections and barriers to accessing healthcare services. They are also more likely to live in rural and remote areas. These factors can all increase people’s vulnerability to HIV and act as barriers to accessing HIV care. An understanding of HIV vulnerability in Indigenous communities must begin with exploring these factors that have arisen from European colonization and the resulting atrocities of genocide, destruction of language and culture, the reserve system, residential schools and so on.

For many Indigenous people, accessing HIV treatment means having to face the stigma of going to a clinic where many of the staff are one’s relatives or friends, which can deter people from getting treatment. A larger problem arises from the number of Indigenous people who migrate to urban areas or move on and off reserve, which can act as a barrier to healthcare. People can obtain provincial or territorial healthcare, but doing so requires a certain level of organization.

The chaos that poverty can create in a person’s life can be astounding: How does one deal with bureaucracies without a safe place to keep their records? How does one get a health card or enter a healthcare system without a stable address? How does one schedule a doctor’s appointment without a phone number where they can be reached? Many people do not know basic information about HIV transmission and infection, or how to avoid contracting the virus. They do not know how or where they would go to get tested.

Numerous studies, such as these, have shed light on the negative impacts that violence, discrimination and poverty can have on people’s health, pointing to the need for HIV care to address these issues.

- Physician and researcher Reed Siemieniuk and his colleagues at the University of Calgary incorporated a domestic violence screening interview into their care of people living with HIV in southern Alberta. Of 853 patients, 34 percent reported abuse. Groups at higher risk for abuse included females, gay men and Indigenous people. The researchers found a connection between a history of domestic violence and delayed access to care, missed appointments and increased use of clinic resources such as social work and psychiatry. Domestic violence was associated with poorer outcomes for people living with HIV.

- A study of more than 1,400 women living with HIV in Canada found that everyday incidents of racism made women less likely to access care. These incidents included prejudiced comments from healthcare providers and disrespect for the women’s cultural traditions. Angela Kaida, a senior author of the study and an associate researcher at the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, says that this finding emphasizes the need for more peers to be involved in the planning and delivery of HIV services and the need for more culturally relevant services.

- Sarah Flicker and her colleagues at York University supported Indigenous youth leaders to produce digital stories about HIV prevention. Their preliminary work showed how important it was for youth to tell their stories, which made connections between HIV and structural violence. They focused on the role of family and Elders, traditional sacred ideas about sexuality, education, reclaiming history, focusing upon strength, cosmology and overcoming addictions. In contrast to conventional public health messaging, the youth emphasized indigeneity and decolonization as key strategies for health promotion.

- Roberta Woodgate and her colleagues at the University of Manitoba interviewed young Indigenous people living with HIV in Winnipeg. They found deeply interconnected social worlds that included abuse, trauma, being part of the child welfare system, lack of housing and hunger interwoven through the threads of these young people’s lives. They concluded that more effort needs to be paid to address the social determinants of health. They highlighted how stigma and discrimination prevent people living with HIV from easily accessing supports and health services. Creative and culturally appropriate forms of outreach are key for reducing stigma and discrimination.

These studies, and Indigenous approaches to healing, can teach us how important it is to pay attention to the social determinants of health and provide culturally appropriate outreach and care for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people living with HIV.

Here are two stories of people from my medical practice that further illustrate these ideas:

Harold was a 17-year-old Indigenous man living in an urban youth shelter. He considered himself lucky to have a warm, dry place to sleep. Our medical residents were providing care to the adolescents who lived at the shelter. Harold had reluctantly allowed us to test him for HIV. When the test came back positive, he shrugged it off. It didn’t mean anything to him. He didn’t expect to live long anyway. His world consisted of figuring out where to sleep at night, how to avoid having sex with people he didn’t like (unless they paid him or gave him weed), how to avoid being robbed or beaten, and how to get to school. The shelter had arranged for him to go to high school, where he was doing well. Harold didn’t trust or believe much of what we had to say. He was quite fatalistic. We arranged free counselling for him with one of our social workers/therapists. Together they visualized a future for Harold where he took advantage of a training program in heating and air conditioning and made good money. It was strange for Harold to imagine a future beyond the next day. He would have had to return to his home reserve to receive supports other than the care we were providing, but he didn’t want to do that because of the abuse he had been subjected to from his family and related to other broken relationships in the community.

Stephanie was a 25-year-old Mi’qmaw woman who had been addicted to heroin since she was 18 and had transitioned to opioid substitution therapy four months earlier. Her recovery was precarious due to her high levels of anxiety, which she had managed previously with heroin. Funerals were more common for her than births—her friends were dying at an alarming rate. Stephanie was seeing us for healthcare because she wanted her buprenorphine. Otherwise, she wouldn’t have come. Like Harold, she was fatalistic. Each day that she awoke, she was surprised to still be alive. Stephanie lived in a studio apartment, which she paid for by doing sex work. She didn’t care if she had HIV or gave it to anyone. Her attitude was that it would serve them right to get infected for sleeping with her. She was angry at her situation. Her childhood had been spent on the reserve with a drug-addicted, alcohol-involved family. Stephanie was fiercely defensive of her friends and family, and to her chagrin, they kept dying. We convinced her to allow us to test her for HIV, and she was unconcerned with the results. She didn’t expect to live much longer, though she occasionally aspired to have a child and a family. In typical Stephanie fashion, she said, “I’m running one fuck ahead of the grave, anyway. What do I care if I slip and fall in?”

These stories highlight the need to change the way our society thinks about HIV and about healthcare. While progress has been made in finding effective treatments and in disease prevention, those who suffer most sometimes receive the least care. We need to speak to HIV treatment and prevention as an act of decolonization and find culturally supportive leaders and messages to reach those who are on the margins. Providing housing can go a long way to helping people start and stay on treatment. Providing easier access to healthcare and antiretroviral medication also makes a big difference, as does supporting activities that promote people’s cultural practices. Involvement of Elders and traditional cultural wisdom keepers in health promotion efforts is also crucial.

What led you to combine Western and Indigenous approaches, to improve the health of your patients? And how do you do that?

I lived the first 30 years of my life with a certain worldview, exactly what the Western model wants you to see and believe. That was good because it taught me how to be a Western thinker and to use my brain to analyze, objectify, categorize and learn all these things that science offers. I learned to practice medicine in that way.

But during med school, I also started to learn about a different way of looking at the world. I sat with people and read and learned about a worldview that really connected with who I was as a person. As I started to understand more about this way of looking at the world and myself and human beings, I saw that there was this huge disconnect between what the Western model had taught me and my understanding of health and the truth. To reconcile the two is difficult.

For example, one straightforward concept is that if you aren’t well, you shouldn’t care for other people. If you’re not a well human and you’re not connected to your spirit and your self and you’re not taking care of yourself, how can you care for others? But in the Western model of medicine, as a resident you sometimes work 36 hours straight, and the system is dominated by authority and hierarchy. After you graduate from med school and set up practice, you’re expected to take on thousands of patients (the average number for a family doctor is 2,000). The average length of time a doctor spends with a client is about 10 minutes. It’s a very high-stress, demanding job, yet we’re expected to provide healing and a path for people to get well. The model for how we do it doesn’t really allow for that.

Since I started working approximately four years ago, I have never had a 10-minute interaction with a patient. I spend a minimum of 30 minutes with each patient, and sometimes up to two hours. I go to their homes when they need me to and I go to the hospital when they need me to. When you are able to do those things, you learn so much more about what somebody needs. And you become like a human to them, not just a doctor.

I don’t do symptom management. I’m always asking, “Why are you having this symptom? Let’s figure that out because in the long term that’s going to be the most beneficial to you.”

An appointment with a patient is like visiting. We talk about their health issues but I also spend time just listening to whatever they have to tell me. Say I’m with someone who has a chronic lung condition. I review their meds, but I always want to know what else is going on. There are all these details and if you let someone talk, you learn a lot—about their family life, their most intimate relationships. How are those doing? Do they have access to good things to eat? Are they fearful for their safety?

I think it would be best if physicians could take on clients really slowly, have time to go through their records, have time to sit with them. But you get into practice and you get thrown all these clients and you’re expected to know everybody’s life story. People get frustrated when you haven’t read over their records. But when am I supposed to do that—on my own time when I’m at home with my child? There are expectations on either side that I think are sick because of the way the system is set up.

There are healers in our community who know a different way. They spend more time with people. There’s also a spiritual component that is missing in mainstream medicine. The way that I combine Indigenous and mainstream healing practices (I do both of those things for myself, too) means that I can better understand what people need so I can connect them with those things.

How do your patients respond?

Some say, “Are you really a doctor?” I have a client who tells me every visit that he can’t value enough the fact that I listen to him. He tells me stories and has valuable things to say and he wasn’t being heard or validated by whoever was serving him previously. That’s the case with many of my clients—they weren’t being heard, so they weren’t being helped.

One of the things we know is that it takes a community. First you have to know yourself really well, and then you can start to take care of others. When everyone is getting well, the community benefits.

It sounds like the person-centred care you’re talking about is important for all people.

Lately I’ve been shying away from labels like Indigenous and non-Indigenous because we’re all human beings. We’re all of the same species and we all have the same basic needs. We are all connected to creation—to the land, to the sun, to everything. This approach is not unique to one group or one place. For us to be really well as human beings, the approach should be the same for all human beings: recognizing that we all have physical capacity, an intellect, emotions and a spirit. Those things need to be valued and addressed equally.

In some ways what you’re talking about is more about how healthcare providers and institutions can adjust their practices, but is there anything that people can do to foster a more holistic approach to their own healthcare?

I always encourage people to use their power, use their voice. When they don’t feel right about the care they’re receiving or they don’t feel heard, they need to say something directly to the provider. If they want to go beyond that, and they’re feeling courageous enough, they can go to the management and HR of organizations. Everyone has a voice and we only create change when we use our voice and our truth.

People complain to their families and friends—“My doctor’s terrible,” “I didn’t feel heard.” Who says that to their doctor? Why can’t doctors be held accountable for the shitty care they provide? Because no one is telling them. Doctors are given so much power and they’re not held accountable. People almost never complain to the person doing the harm. People are afraid but everyone has to work on their own fear. You have a voice, please use it.

I want to know if you don’t like my care. Healthcare is a publicly funded system, so the public has a say. If you’re using your voice laterally—to your family or friends or community—but not upwards, I would challenge people to be honest with their providers about how they feel about their care. The provider might react poorly because they might feel triggered but it’s still important. The truth is always felt. They’ll feel it in their heart and their spirit and they’ll think about it.

As doctors, we’re not better or stronger. Our goal as doctors is to help people.

I am an Indigenous physician. I am trained in Western medicine and I am training in traditional medicine with my teacher Kathy Bird. I am an Indigenous person first and foremost and I feel a void when it comes to being able to adequately provide care for my Indigenous peoples without gaining further knowledge about our Indigenous ways of healing. As I am on my journey to understanding more about who I am as an Indigenous person, I realize others are on their own journey as well. It is very important to establish who we are in every context but in the healthcare setting I feel it is even more essential. Colonization has caused many wounds. It is thus very important to decolonize even healthcare practices. I think this vignette highlights this quite eloquently:

Many Indigenous patients we saw in clinic were experiencing deeply distressing situations—poverty, threats to their own and to their loved ones’ safety and well-being, chronic pain, children in foster care. Western medicine does not address many of these issues, which are a big part of a person’s health and well-being. Some patients lamented a lack of access to ceremony and to traditional medicines like cedar or sweet grass, as they now lived far from their home communities and elders. They were invited to share in smudging as part of their primary care appointment and they were presented with medicines to take with them for ceremonial use at home.

The reasons for these individuals’ suffering and their disconnection from traditional healing practices and materials can be traced to colonization and current systemic racism. Many people with HIV share this terrible legacy. The use of ceremony and the provision of traditional medicines is a deeply symbolic, highly powerful gesture of decolonization and healing.

Many non-Indigenous people with HIV have also lived through their own traumatic experiences or are dealing with distressing situations and need help finding their paths to healing.